Black History Month and beyond: celebrating Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson, grandfather of Black basketball

Black History Month and beyond: celebrating Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson, grandfather of Black basketball

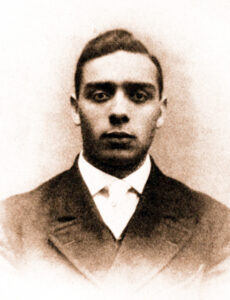

Sports historian, educator, administrator, coach, athlete and Civil Rights activist Dr. Edwin (E.B.) Bancroft Henderson is celebrated by the University of the District of Columbia as one of its national treasures. Recognized as the “grandfather of Black basketball,” Henderson’s contributions are being immortalized on UDC’s campus through a statue that will be made in his image and a sports complex renamed for him.

Henderson introduced his hometown of Washington, DC, to basketball in 1907 when the game was less than two decades old and segregated. In recognition of his contributions, UDC named the Edwin Bancroft Henderson Sports Complex on Dennard Plaza last year and will unveil a statue in his likeness in June.

Henderson earned his teaching certification in 1904 from Miner Normal School (a predecessor institution). He earned his bachelor’s at Howard University, a master’s degree from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in athletic training from Central Chiropractic College in Kansas City, Missouri. Henderson became the first Black man to receive a National Honor Fellowship in the American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation.

For 25 years, Henderson served as the director of the Department of Physical Education for the District of Columbia’s segregated Black schools. Among the many students that Henderson coached, taught and mentored were Charles R. Drew, Montague Cobb and Duke Ellington.

Henderson learned the game of basketball while attending a summer program for gym teachers at the Harvard School of Physical Training in 1904.

After returning to Washington, DC., he was turned away from attending a basketball game at the Central YMCA. He recognized the potential in the game and went to work to bring the game to the District.

Henderson introduced the game to Black students in the segregated public school system in DC. It was the first time African Americans had played basketball on a wide scale, earning Henderson the distinction as the “grandfather of Black basketball” and the District of Columbia as the “birthplace of Black basketball.”

By creating leagues and associations for Black athletes and referees when they didn’t exist, Henderson created the infrastructure for African American participation in athletics.

He helped establish the Interscholastic Athletic Association (ISSA) to foster high school and college athletics in Washington’s Black community. The ISAA became the governing body for sports, with basketball as a top priority. Teams playing under the ISAA flourished, and Henderson’s own 12th Street YMCA team went undefeated in 1909-1910, earning the unofficial title of Colored Basketball World Champions. Henderson devoted his entire life to developing, promoting and improving the game.

Through the I.S.A.A., Henderson organized and promoted intercity play between Black basketball teams along the Mid-Atlantic coast, especially between New York and Washington, DC.

He organized a basketball team for the local Twelfth Street Colored Y.M.C.A., leading to an undefeated season and the 1909-10 Black national title.

A year later, seeking more fans, Henderson successfully petitioned nearby Howard University to adopt his 12th Streeter squad as its first varsity basketball team.

He then coached that team to win the 1910-11 Colored Basketball World’s Championship title, again going undefeated.

During this time, Henderson also co-edited the Spalding Official Handbook for the I.S.A.A., published from 1910 to 1913. The Spalding I.S.A.A. series gave a comprehensive account of Black participation in all major sports and remains a rich source of early historical information about African Americans in basketball.

In December of 1907, Henderson staged the first known Blacks-only basketball game. Then he started raising money for the city’s first YMCA for Blacks. That same year, he created a league for African American basketball teams in DC.

Henderson pioneered physical education programs in Washington’s segregated public schools. He also improved local sports facilities, organized the first track meets for African American high schools and colleges and created athletic associations to foster a culture of athletic competition in the Black community.

He lived in Fairfax County, Virginia, where in 1915, he organized the Falls Church branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), its first rural chapter. He fought racial discrimination in local housing and law enforcement practices; battled segregation in transportation, schools, and other public facilities; and encouraged voter registration.

During the 1950s, Henderson served as president of the NAACP Virginia state conference. While making basketball courts his classroom and NAACP work his vantage point for civil rights advocacy, Henderson was met with threatening letters and telephone calls, cross-burnings, and Ku Klux Klan visits. Throughout his life, thousands of Henderson’s letters to the editor on Civil Rights issues were published in The Washington Post.

To raise awareness of talented African American athletes, he published The Negro in Sports (1939; rev. ed. 1949). Henderson was posthumously inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2013.

Awareness about his contributions to the game of basketball continues to gain attention thanks to efforts from UDC Board of Trustee members Barrington Scott and Antoinette White Richardson, who initiated the renaming of the UDC sports complex in his honor and spearheaded the erection of a statue in his likeness in June, along with an ongoing campaign to provide summer sports camps and scholarships for students.

Henderson was married for 63 years to educator Mary Ellen Henderson. February 3 marked the 46th anniversary of his death.

Learn more about his legacy from his grandson, Edwin B. Henderson II, in an interview with Dr. Sandra Jowers-Barber, director of the Humanities and Criminology Division at UDC Community College and host of UDC Forum.

The program will air on UDC Cable Television (UDC-TV) every Monday, Wednesday and Friday in February. In Washington, DC, UDC-TV can be viewed on Comcast Channel 98, RCN Channel 19 and Verizon Channels 19 and 21. The program will also be available on demand on the UDC-TV YouTube Channel and UDC Forum Playlist.